Sign up to our free Google Ads email course.

7 days, 7 lessons. Everything from how to structure your Google Smart Shopping campaigns to ad testing, and YouTube ads excellence. Sign up and level up your Google Ads eCommerce game.

Why investors love DTC startups

For investors, it’s easy to see why the DTC love-in has reached peak. More often than not, these startups are there to give the corporates a bloody nose, by fixing broken customer experiences. The likes of Harry’s, for example, took on an unfair industry that was calling out for innovation in the way people buy, and ultimately delivered on their promise to provide better value for money than big boys such as Gillette. Consumers and VCs alike took notice, and other industries were quickly targeted.

Being the Warby Parker or Harry’s of X became a thing. Investors perceived that customer acquisition could quickly be scaled by viral videos and word of mouth, and marketing costs could be kept in check by zeroing in on tightly-defined customer segments. The formula of complacent industry + tired consumers + jaw-dropping retailer markups was an opportunity not to be missed for many new DTC entrants.

Moving from one product to many

However, it’s one thing to get customers through the door. It’s quite another to get them to keep coming back, again and again. And for DTC brands, that bit is quite crucial to their business model. Take mattress brand Casper for example. Most consumers in the market for mattresses will buy one every ten years or so, due to the durability of the product. For Casper, this presents a specific problem, as their sky-high customer acquisition costs – rumoured to be on average, 29% Cost of Sale – mean that they need to be bringing customers back time and again to justify that kind of outlay on marketing.

To do this, it needs to switch gears, and diversify. It now sees itself as the Nike of the sleep economy, selling everything from sleep aids, to pillows, scent devices, and digital apps. It’s not alone with this approach, with Warby Parker expanding to contact lenses, shaving startup Harry’s moving to offer general grooming products, and luggage brand Away diversifying to a plethora of travel accessories including post-travel skincare. The new rules of DTC have moved on from simply disrupting slow-to-innovate industries with a shinier, cheaper product than the Old Guard; now, they need to follow that up by expanding share of wallet amongst their customers to justify the many millions spent on acquiring those customers in the first place.

An unhealthy reliance in paid marketing

And when you look deeper into the numbers, you really begin to understand just how flawed the marketing machine is for some of these businesses. Within the DTC business model, customer acquisition is really just shorthand for paid marketing across both Facebook and Google ecosystems. These two platforms encompass Facebook, Instagram, Google search and display networks, and YouTube – all primary DTC marketing channels.

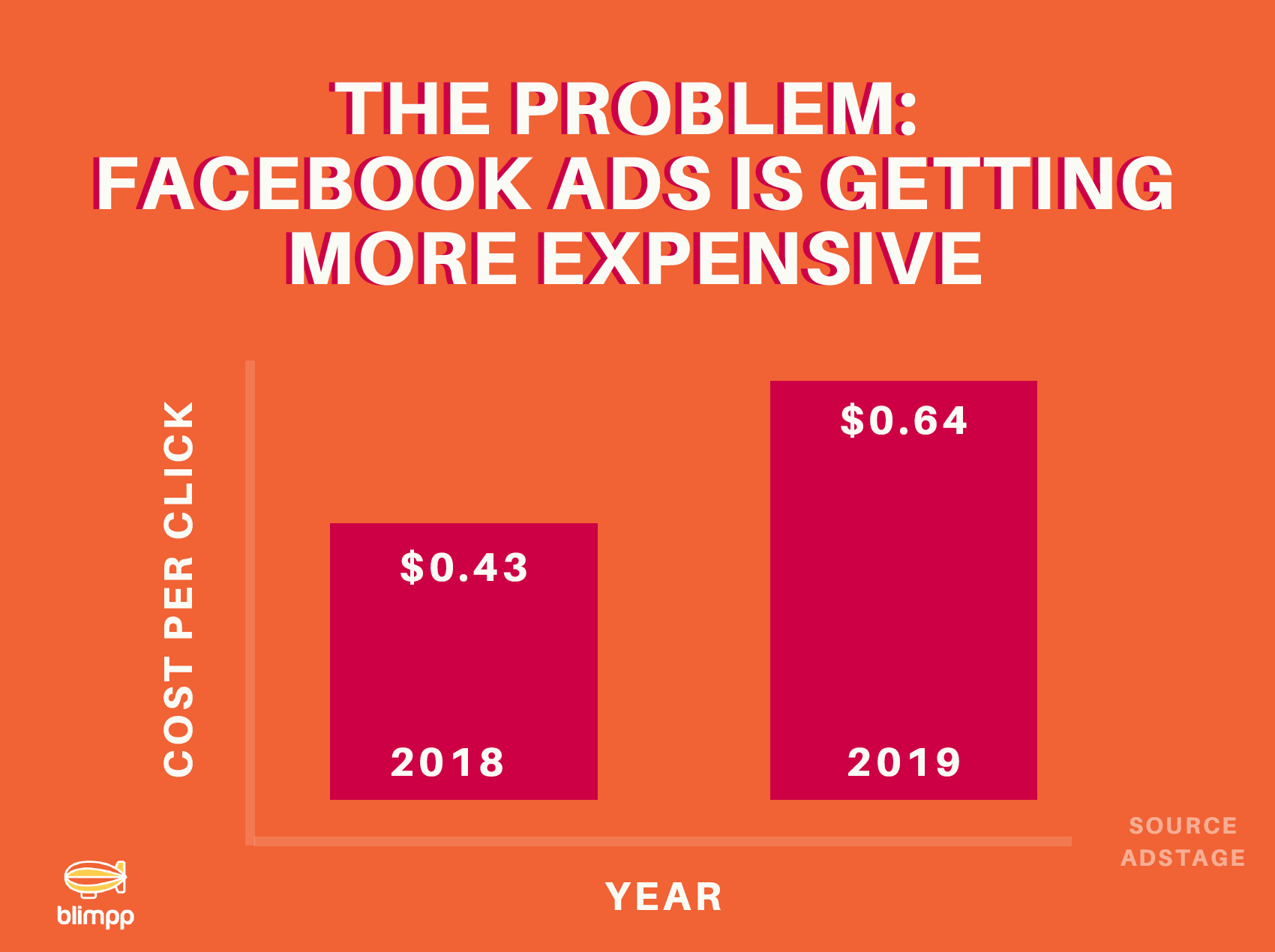

As more companies join the party, the race for consumers gets ever more competitive, driving up click costs across each of these advertising platforms. Take Facebook, for example, which according to AdStage, saw an average click cost inflation of 49% between Q2 2018 and the same period in 2019. Platform saturation is a real thing, especially given that the a lot of these DTC companies are armed with similar amounts of marketing cash, each targeting similar customers, across similar looking ad placements.

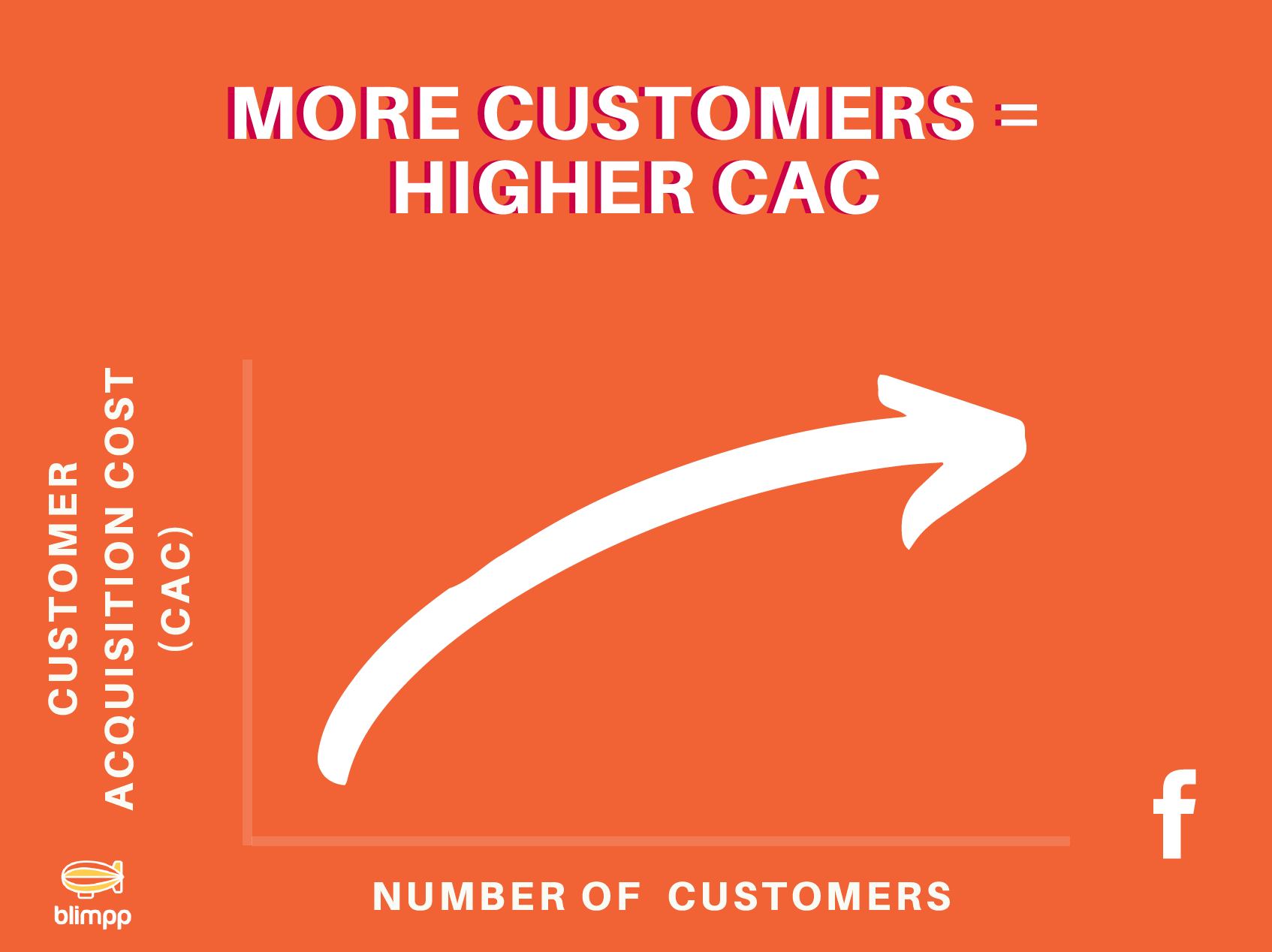

Escalating click costs are just one reason why Facebook in particular, becomes less efficient the more you use it as a customer acquisition channel. The broader you go with your audience targeting, the less relevancy exists between your target customer’s needs, and your product. For example, you could find your average customer acquisition cost at a pretty healthy £100 for the first 100 customers you acquire. But this can quickly escalate as you scale and widen your targeting, with customers 101 to 1,000 costing you perhaps £125 on average to acquire, customers 1,001 to 1,500 costing £150 per acquisition and so on. It can suddenly become unsustainable to acquire customers, yet aggressive customer growth is exactly what VCs demand when they pump money into a company. The hope is that if you pay over the odds acquiring customers today, you can up-sell and cross-sell your way to profitability tomorrow.

Tying marketing performance to profitability before growth

With all this in mind, DTC are increasing prices to offset some of this cost. Brandless, a now defunct DTC startup specialising in fast-moving consumer goods, raised its prices from $3 per item to $9 per item due to trading difficulties encountered as as result of inefficient acquisition model. Having raised a total of $240 million in May 2019, it ceased operations in February 2020, citing fierce competition and business model inviability in the direct-to-consumer market. Focusing on rapid customer recruitment literally killed their business, as they ignored for too long the need to focus on that basic business principle: turning a profit.

Emerging DTC brands need not make these same mistakes, but it will take a very different approach to what has gone before.

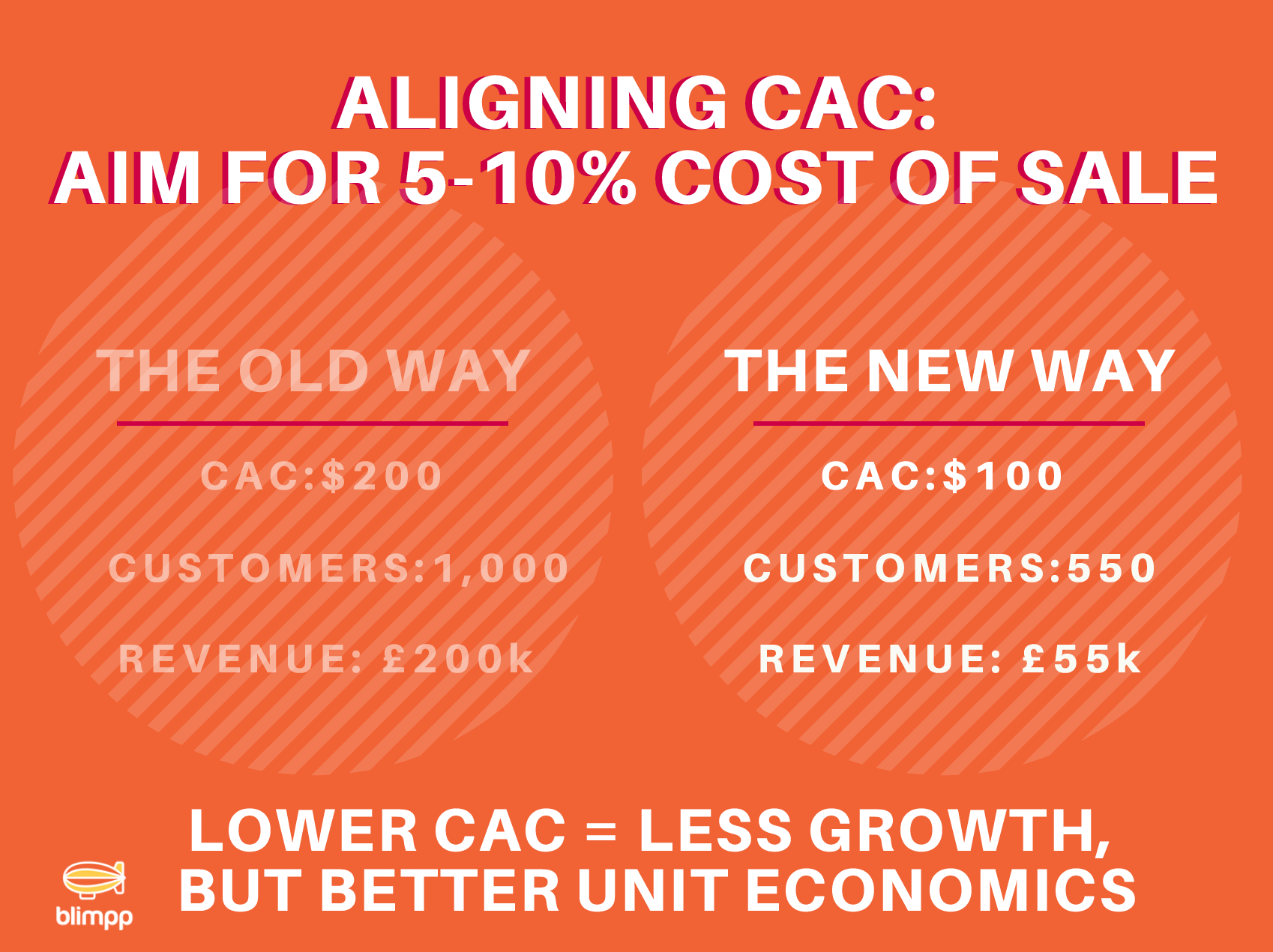

Tying paid marketing performance to profitability, and at the same time, reducing reliance on paid marketing as an acquisition channel, may be the only way to make DTC businesses function as self-sustaining entities. For example, Casper’s estimated average customer acquisition cost is $290, which against the context of an estimated average order value of $1,000, especially when Casper themselves freely acknowledge a return rate of 20%. Reducing customer acquisition costs in half would mean focusing efforts only on those people who are most likely to convert, which would improve conversion rates and improve acquisition efficiency as a whole. The down side to this approach of course, being that they would be targeting fewer people, so the overall number of customers would be less.

Building a retention engine

Building a community around your brand

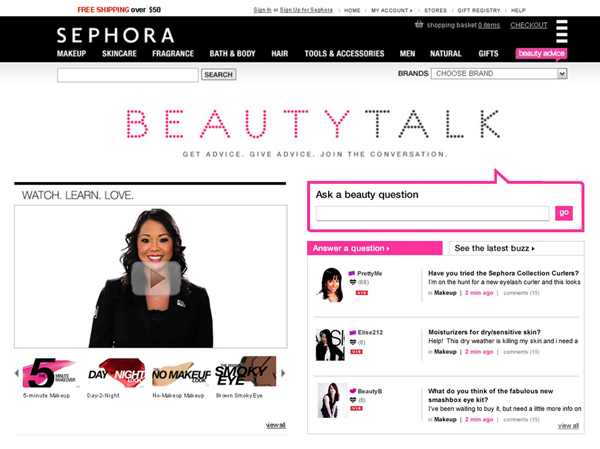

In similar vein, building a community around your product can drive positive business results, in a non-salesy, consumer-centric kind of way. One company that knocks this approach out of the park is beauty brand Sephora, which created a community on its website called Beauty Talk. This forum provides a platform for cosmetics enthusiasts to discuss all things beauty, including products, confidence, and self-image. Beauty Talk is home to over a million user posts and replies, ranging from foundation talk to personal stories and entirely off-topic threads, but is a community which keeps Sephora’s customers coming back to their site.

DTC brands could learn much from their approach, and potentially there’s scope to go a step further. There’s nothing to stop a Casper or Dollar Shave Club setting up a Facebook group geared around common customer needs, before they even think about buying a mattress or sign-up for a shaving subscription. Yet this not something that most brands will entertain, as they see themselves as a revenue-generating entities first, and content providers second. The future winners in this space will be the ones that invest in defining a problem and build an eco-system around that encompassing content, communities, and of course, product.

Don't let your CAC be the new rent

And this type of approach is exactly the anti-thesis of what DTC brands are today. A perception that paid marketing is the only game in town when it comes to delivering on customer acquisition has led to an over-reliance on it. VCs are so focused on growth numbers, that this is the only viable short-term option, perhaps alongside TV, outdoor, and press. But the DTC brands that will here in five or ten years from now will be the ones that have invested in organic channels, not as a replacement for paid customer acquisition, but as a mechanism to regain some control of their business model from the likes of Facebook and Google.

Ultimately, companies will have no choice. According to Daniel Gulati, a partner at Comcast Ventures: “CAC is the new rent. In other words, for companies reliant on paid marketing, their customer acquisition cost is a lot like paying for brick-and-mortar stores in the old model, or selling wholesale. Essentially, this undermines one of the most basic precepts of the DTC movement, that these companies are cutting out the middleman and therefore can afford to charge much less for higher-quality goods.”

Essentially, direct-to-consumer is a bit of a false label, as Facebook and Google have essentially become the storefront for these brands. And if that’s the case, price is now longer a USP, especially when you add this cost to those of shipping, returns, and other overheads.

All of a sudden DTC becomes less of an attractive proposition for all concerned – founders, VCs, and most of all, customers. Something needs to change.